Live and study in the beautiful and renowned city of Oxford. A semester at Scholarship and Christianity in Oxford (SCIO) utilizes expert tutors, offers endless scholarly resources, arranges library access, and provides a formative academic program with enriching research opportunities, all in the context of a commitment to integrate the pursuit of academic excellence amid deep Christian commitments. We invite you to walk the same paths and study in the same places as some of the greatest scholars in history.

Connect With SCIO

Dear Prospective Scholars,

Thank you for looking at Scholarship and Christianity in Oxford’s (SCIO) offerings. Whether you are considering a semester or summer programme, we have great opportunities awaiting you.

Oxford: the name that conjures up notions of a great medieval city full of dreaming spires and stunning architecture, idiosyncratic practices, renowned authors who have made their way into the canons and literary reading lists, great theological debates, and major politicians. The mythic abounds. But even more, the concrete reality of a world-class scholarship is omnipresent: with research; major scientific discoveries; scholars across the disciplines whose works inform most, if not all, academic libraries; students sitting in cafés debating perennial issues and newly breaking ideas alike; and a rich and vibrant student life including music, sport, and drama.

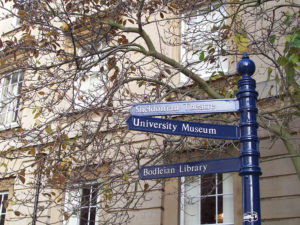

Come sit in a tutorial where you meet one-on-one with a tutor engaged in serious conversation, testing ideas and joining together as junior and senior scholar. This is a learning experience like no other: there is no hiding (for tutee or tutor!), and you probe and digest ideas, coming to your own conclusions with the requirement to demonstrate that your view is valid and solid, even where it diverges from the views of other scholars or your tutor. To accomplish that goal, as a researcher yourself, you will have access to one of the world’s great libraries, the Bodleian Library with holdings in excess of 13 million items.

Join a rich community of scholars who share life together in a variety of forms: from the life of the mind; to cooking a meal together; to traveling on SCIO trips to interesting places like Bath and Hampton Court Palace; or making your own forays into London, up to Scotland, or over to the continent during the mid-term break. Join, too, a community of faith that is engaged in serious learning, affirming the ability to participate in scholarship as Christians dealing with difficult and profound issues.

SCIO offers the opportunity to participate in a great academic experience, prepare for graduate studies (for those headed in that direction), and build your CV with a recognized educational experience that matters to academic institutions and employers alike. As you review the materials on the website, we hope you see the possibilities and consider joining us. With SCIO staff, you will have a resource at hand to help you put your best foot forward as you apply.

Yours with every best wish,

Stan Rosenberg

Executive Director

Designed specifically for students seeking an academically rigorous and robust experience, a semester at SCIO seeks to brighten the brightest of minds. In tutorials, students meet one-on-one with acclaimed Oxford scholars (often including widely-published authors, historians, former international ambassadors, and other celebrated scholars) to go head-to-head on subjects within the disciplines of history, literature, languages, philosophy, musicology, art, science, and more. Tutorials, lectures, and seminars are equivalent to upper-division courses, and students are expected to do advanced-level work. More specific information about the coursework offered at SCIO can be found in the table below.

| Required Courses | Credits |

|---|---|

| 6 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 4 | |

| Total Credits | 17 |

British Culture Courses

C.S. Lewis and the Classics

When C.S. Lewis arrived in Oxford in 1917, he came to study Classics: the literature, history, and thought of ancient Greece and Rome. He was an atheist, and was fascinated by the pagan mythology of the classical world, and this was a fascination that never left him. In fact, it was through this love of mythology that he finally became a Christian, and he drew on this rich classical heritage throughout his career and a teacher and writer.

Lewis was a star student, and earned a prestigious ‘double first’ degree before moving on to a career in English literature. (Tolkien, by contrast, also studied Classics at Oxford, but earned mediocre grades and dropped out of the course.) Lewis’s classical education formed him: one cannot read far in his books without coming across a reference to an ancient Greek story, or a Latin quotation, and in this course we will be examining the enormous influence that Classics had on Lewis’s life and thought.

The only classical god to appear in Narnia is Bacchus, the god of wine and license (in Prince Caspian); why did Lewis let him in? This is one of many intriguing questions we’ll be addressing. In fact, Bacchus (or Dionysus) was deeply interesting to Lewis, and closely connected to his views of Christ; and there are many other classical elements in the Narnia books, such as fauns and centaurs, that we’ll investigate. We will consider the role mythology played in Lewis’s understanding of the world, and, particularly, in his conversion to Christianity. We will look at one of Lewis’s favourite poems, Virgil’s epic Aeneid, and consider how its picture of wanderings in search of a home related to Lewis’s ideas of the Christian experience. We will examine Lewis’s final novel, Till We Have Faces, in which he retold the myth of Cupid and Psyche, a task which he had been trying to do for most of his life.

Lewis’s love of the Classics pervaded his thought, and in this course we will be looking at its influence in his fiction, his literary criticism, his poetry, his letters, and his Christian apologetics. Equally exciting is the chance to examine the Classical world through Lewis’s eyes. There is a great deal of pleasure to be derived both from reading Lewis and from investigating the classical world, and in addition to this students will gain a much deeper understanding of Lewis as a writer and as a Christian.

Contemporary British culture: history, politics, and society

Britain in the twenty-first century is a country looking for an identity. Having left the European Union in January 2020 Britain needs to find new policies at home and a new role abroad. Having ‘regained our national sovereignty’, as Brexit supporters put it, Britons now need to decide how to make use of that sovereignty. Covid-19 has forced further reappraisal of what matters to Britons: should the country return as soon as possible to how things were before, or is this a singular opportunity to reimagine polity and society, giving priority to the things which lockdown showed us were valuable?

This course takes a succession of British tropes to probe what they tell us about contemporary Britain and how they shape discussions of the nation’s future. What, for example, does the Union Jack (strictly speaking the Union flag) reveal about the constituent parts of the United Kingdom and their relationship with the whole? What does the British cup of tea tell us about the nation’s role in global trade and colonisation? What does the king tell us about Britain’s version of democracy? What can we learn from the James Bond novels and films about Britain’s fear of international decline and its sense of superiority? In what way are soccer, cricket, and Wimbledon windows on to British class, ethnic, and regional cultures? What does Britain’s ‘green and pleasant land’ reveal about conservation, rural life, and leisure in Britain? What does Westminster Abbey, the national pantheon, reveal about Britons’ relationship to the past? What does a country church tell us about religion in Britain? Why on earth do Britons talk about the weather all the time? What does the BBC reveal about the English language, Britain’s role in the world, free speech, and British values? What does the Channel Tunnel tell us about Britain’s relationship to Europe?

With these and other tropes we explore Britain and its inhabitants, searching for explanation rooted in the past, and considering what the nation might look like in the future.

Creative Writing

If you study creative writing, you will read canonical writing with an eye to techniques you can make your own in writing that will be workshopped, one-to-one, with the tutor. In the prose section of the course you’ll read a short story by James Joyce, noting his stealthy satire of society and literary convention, then take a boat out on the stream of consciousness of Virginia Woolf. Can you pick up her knack of jumping from one person’s point of view to another’s on the turn of a comma?

The poetry section includes looking, though T.S. Eliot’s ‘The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, at ways of communicating through music and repeated sounds. (How do you feel different saying ‘is it/visit’ compared to ‘go/Michelangelo’?) You’ll also, through reading the work of Philip Larkin, learn the right way to use metre and rhyme; the lines round a repeated stanza form make the shape not, as many think, of a ‘constricting’ container, but of a fabulous tennis court at Wimbledon.

The one-to-one tutorials are fundamentally a conversation, with a great deal of flexibility in what is discussed. Throughout the course, the emphasis will be on the pleasure of reading and the craft of writing, and on the triple literary aims of teaching, moving, and delighting both writer and reader.

Dark imaginings: the gothic novel from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century

This course traces the development of the gothic movement from its origins in Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) – the first ‘gothic novel’ – to its interrogation of fin-de-siècle anxieties in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

The initial impulses of the gothic movement were architecturally driven, and its fondness for shady precincts and supernatural happenings was a reaction to the dominance of Enlightenment rationalism. By the end of the eighteenth century, it had developed into natural territory for the literary response to the violence and terror of the French Revolution. As a transgressive sub-genre of the novel, it was anti-Catholic, anti-nostalgic, and anti-aristocratic, with conventions including lordly villains and persecuted maidens, suppressed secrets and illicit acts, pursuits and imprisonments, supernatural manifestations, victories of chaos over order and nature over man’s creations, and a heightened version of physical and psychological experience.

Early novels to be discussed include Ann Radcliffe’s highly influential The Romance of the Forest (1791), Jane Austen’s witty and complex parody of the genre, Northanger Abbey (1817), and Mary Shelley’s mythical exploration of man’s Promethean nature in Frankenstein (1818). Students will go on to explore the Victorian evolution of the genre to reflect nineteenth-century concerns about religion, race, gender, imperialism, and cultural degeneration through Charlotte Brontë’s domestic re-imagining of the gothic romance in Jane Eyre (1847) and Oscar Wilde’s aesthetic gothic in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891).

Each novel will be discussed in its historical and cultural context. Questions addressed along the way include: How does art relate to the gothic? Why do we remain fascinated with the forbidden and delight in being terrified? What is the difference between terror and horror and the relationship between past and present? How and why does the gothic genre keep reinventing itself? By the end of this course, students should have acquired an understanding of one of the most popular and beguiling genres of the novel, which continues to exert its fascination today.

Faith and reason in the British enlightenment

The Enlightenment saw the rise and triumph of reason as the supreme power in many spheres. One area which – perhaps inevitably – provoked much discussion was religion. For some, this provided an opportunity to attempt to demonstrate a sound rational basis for religious belief; for others, it led to the challenging of old certainties.

In this course, we’ll examine the application of reason to matters of faith during this period. Our focus will be on the work of three British philosophers in the empiricist tradition, who were at work during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume.

We’ll begin by exploring the key relationship between faith and reason. The two are sometimes contrasted with each other, but philosophers such as Locke argued that in fact they are complementary concepts, and need not be seen as in opposition to each other. A major question which exercised many thinkers was whether God’s existence can be proved, so we’ll also examine Locke’s version of the cosmological argument, Berkeley’s idealist philosophy (which he believed offered an antidote to atheism and irreligion), and the sceptic David Hume’s criticisms of the argument for design. There will also be a chance to look at some responses to these authors, from both contemporary writers and more modern ones.

Although written over two centuries ago, these texts raise crucial questions which remain just as relevant today, and this course provides an opportunity to harvest some of the riches of insight offered by great thinkers of the past.

Intellect and imagination: the rational religion and theological stories of C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis is known to millions around the world as a writer of fantasy literature (most famously The chronicles of Narnia), and as someone with a gift for presenting Christian theology to a large popular audience, through works such as Mere Christianity and The problem of pain.

On the face of it, these two aspects of his writing – the imaginative and the intellectual – may seem quite different. But in this course, we’ll explore how the two work together and harmonize, and how fiction can in fact be an ideal vehicle for conveying complex concepts. We’ll look at a number of key strands of Lewis’s theological writings, examining both what he said and how he said it: we’ll delve into the arguments advanced and the claims made, and we’ll also consider what difference the form of the writing makes.

You’ll have the opportunity to investigate a variety of themes: Lewis’s trilemma (otherwise known as the ‘mad, bad, or God argument’!), his argument from desire (which suggests that the yearning we find within ourselves is an indication we were made for another world), his views on Christianity and myth, the problem of suffering, and heaven and hell. We’ll look at both his non-fiction books and essays, and his imaginative works, such as The great divorce.

You’ll be encouraged to apply your own analytical skills to Lewis’s writings and to some of the various responses to him (both positive and more critical), as we investigate his claim that religious truth requires a response from the whole person: that it must be both assented to with the reason and embraced by the imagination.

J.R.R. Tolkien: Oxford’s creator of other worlds

Oxford has been a centre of scholarship for centuries, and since the nineteenth century it has also boasted a considerable number of acclaimed and popular writers of what has come to be known as fantasy literature. Nonetheless, by the early twentieth century, the philologist and literature professor J.R.R. Tolkien felt that such fiction had fallen out of fashion and been handed over to children — ‘relegated to the nursery’. He set out to reclaim high fantasy for adults, believing that it had major literary merit and should not be dismissed as escapist or childish. In fact, he argued that fantasy can fulfil humanity’s ‘profounder wishes’, providing readers with a fresh perspective and a world stripped of its dull familiarity. Tolkien continues to dominate the genre in prose and film, setting the standard not only in fiction with The Lord of the Rings, but also in critical commentary with his 1939 lecture ‘On fairy-stories’, which remains a definitive piece of criticism.

In this course we will examine Tolkien’s life, his literary influences and source materials, the major works of fantasy, and selected critical responses, both positive and negative. For example, though Middle-earth was his attempt to create an authentic mythology for England, it has been criticized for its seeming lack of ethnic and gender diversity. Tolkien was shaped by his education, his traumatic experiences in the First World War, and a life spent in what was then the predominantly white, upper-class, male environment of Oxford. Sessions will therefore include discussion of the biographical, historical, and cultural contexts of his writings and their effect on the racial, gendered, regional, and socio-economic elements in his characterization and created world.

Notwithstanding, why does the Middle-earth legendarium continue to fascinate readers and to inspire new generations of fantasy writers? Are the wildly successful film adaptations of these books a testament to Tolkien’s vision or is Christopher Tolkien correct when he claims that the ‘commercialisation has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing’? These are some of the questions we will consider.

Jane Austen in Context

Since the publication in 1811 of a novel called Sense and Sensibility, ‘by a lady’, the works of Jane Austen have enjoyed both popularity and critical acclaim, and scholarly interest shows no sign of waning.

Nor does what can be described as a popular mania for all things Austen, especially in film and television: the so-called ‘Austen brand’ is thriving. In this course will find out why, examining Austen’s life and writings to assess her novelistic technique and development and her place among women writers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In addition to studying the major novels, we will look at Austen’s juvenilia and place each text in its literary and historical context, examining, for example, the eighteenth-century cult of sensibility when we discuss Sense and Sensibility and the contemporary vogue for gothic novels when we study Austen’s burlesque of the gothic genre, Northanger Abbey.

Other themes that will be covered include Austen’s treatment of class, economics, education, female friendship, courtship, and politics. Finally, students will be given the opportunity to assess selected screen adaptations of the novels to decide if they testify to the timelessness of Austen’s wit and the ongoing relevance of her social satire, or damage her reputation as a writer with the addition of romantic elements that distract from the commentary and limit Austen’s appeal to a female audience.

Oxford and the pursuit of beauty: art and criticism in the 19th century

Two of the greatest Victorian art theorists, John Ruskin and Walter Pater, studied and taught at Oxford, and their influence both in the city and further afield was immense. While Ruskin sought to link the visual arts to a serious moral vision of society, based in his evangelical upbringing, Pater preached the gospel of Aestheticism, pursuing beauty as an end in itself and advocating art for art’s sake. Their writings are theoretically challenging and controversial, as well as being masterpieces of prose, and we will examine their ideas and put them in their wider context.

We will examine the influence of these ideas as well. Ruskin’s love of medieval society and gothic architecture influenced buildings and painting in Oxford, where the battle between the classical and gothic styles was seriously and bitterly pursued. His ideas spurred revolutionary young painters: the original PreRaphaelites; and subsequently William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, both undergraduates at Oxford, whose work laid down the foundations of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Walter Pater’s elevation of beauty made him a pariah in conservative Oxford, but his shocking ideas enraptured young people looking to break free from stuffy social expectations. Oscar Wilde, another Oxford undergraduate, was captured by his spell, and worked out his philosophy in masterpieces of creative literature.

We will study at the buildings in Oxford whose design reflects competing ideologies about art: the Martyrs’ Memorial, the Ashmolean Museum, the University Museum, and Keble College, among others. We will examine the artists who worked in Oxford, from professionals such as Dante Gabriel Rosetti to amateurs such as the passionate photographer Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (otherwise known as Lewis Carroll). We will also consider patrons, such as Thomas Combe, printer to the university, whose love of PreRaphaelite art combined with his commitment to the High Church and whose prize painting, Holman Hunt’s “Light of the World”, hangs today in Keble Chapel.

In this seminar we will look at revolutionary texts about the place of visual art in society: texts which propose opposing views about what is valuable in art and which still have an impact on the way we look at art today. We will also look at the art that inspired and was inspired by these writings, aiming to enjoy it, understand it, and place it in its historical context.

Psychology and literature: from Margery Kempe to Sylvia Plath

It has often been said that there is a fine line between genius and insanity and the relationship between literature and mental health has been of intense interest to both literary scholars and psychologists.

This seminar will explore mental illness and instability in several major authors, focusing on Margery Kempe, a medieval housewife and mystic who became the first autobiographer in English; John Bunyan, the seventeenth-century author of Pilgrim’s Progress; John Clare, a nineteenth century nature poet who became incarcerated in an asylum; and two key twentieth-century female authors, Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath. Both iconic figures in the history of women’s writing, Woolf and Plath each struggled with extremes of mood and ultimately committed suicide. We will read their writings in the light of psychological theory and of cultural and feminist contexts.

Complex questions will emerge as we study these authors; what is the true nature of ‘mental illness’? To what extent is it valid or helpful to apply modern psychology to writers from a very different age? How is emotional disorder expressed within the texts themselves? To what extent can other modern theories, especially feminism, help us in encountering these key authors, their lives and their legacies? Led by a literary scholar who is also a psychologist and psychiatrist, this seminar will bring unusual insights to the study of these distinctive texts.

Science and Religion

Science and religion are two of the most powerful forces that shape contemporary life. Yet, a popular perception persists that these disciplines are necessarily in conflict with one another. As Alister McGrath notes, some scientists and religious believers view science and religion as ‘locked in mortal combat’. Those who subscribe to this ‘conflict model’ to depict the relationship between scientific and religious modes of thought often reference historical events such as the persecution of Galileo by the church, the debate in 1860 between Thomas Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, (which took place in Oxford!), or the Scopes trial of 1925 as evidence to support their position. Some vocal dogmatic scientists today call for the cessation of religion in light of the developments of modern science.

There are complicated questions to address here: must science and religion be viewed as necessarily in conflict with one another? Are there other models to help us understand how these disciplines ought to relate to one another? Does science raise questions that point beyond itself? Can theological questions be informed by scientific disciplines?

This course draws on historical and theological scholarship to investigate key issues in science and religion. We begin the course by examining the historical events often used to support the notion that science and religion are in conflict—Galileo, Darwin, and the Scopes trial. As we will see, studying these events in more detail makes it more difficult to interpret them as straightforward examples of science and religion at war with one another. The course will also provide an opportunity to examine more recent questions at the intersection of science and religion: does evolution undermine the biblical notion that humans are ‘made in the image of God’? Does the concept of original sin need to be reformulated in light of developments in evolutionary biology? Can God act in a world increasingly predictable to science?

Sharing a crowded planet: thinking about nature, ecology, religion, and ethics 1750–1960

Our planet is small, beautiful, and crowded. We might expect that Christians, with their duty to be good neighbours, would be at the forefront of efforts to keep it beautiful and share it generously with neighbours. Yet in a famous polemic in 1967 Lynn White Jr declared that, as ‘the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen… Christianity bears a huge burden of guilt’ for the present environmental crisis.

The article became received wisdom in environmental studies, leading to Christianity’s being considered the problem, not part of the solution, and to a focus on the work of those who found in nature itself the prospect of peace, fulfilment, and even salvation.

Yet the roots of nature conservation, particularly in the old world, were often Christian: the UK’s foremost conservation charity, the National Trust, for example, was founded by three devout Anglicans. Moreover conservation was impelled not thwarted by anthropocentrism: the Commons Preservation Trust, for example, the UK’s oldest preservation society with many Christians among its founders, campaigned to save commons for, not from, people. Can White’s argument and empirical research about early naturalists be reconciled? Can attentiveness to Christian motivation enrich our understanding of nature conservation? Can the experience of Christian nature conservationists give us a language for discussing the relationship between Christianity and ecology, and a basis for constructing our own authentic ethics of ecology and conservation? By close reading of nature texts we move the discussion back in time to consider a new starting point, to recover a Christian environmental ethics recover from conservation’s roots and adapt it for today’s purposes.

Academic Concentrations

There are three ways to put together a plan of study at Oxford so that a coherent and individual programme can be followed by each student.

Thematic Concentrations

Perhaps you are interested to see ways in which you can specialize your studies by theme or time period through an interdisciplinary focus. Thematic examples include “The Ancient World,” “Philosophy and the Human Mind,” “Religion and Literature,” and more.

Disciplinary Concentrations

Putting together studies in this way follows the traditional model of learning: working within one discipline but specializing within it. Students select a primary and secondary tutorial from one of the disciplinary lists, do a research project in the same discipline as the primary tutorial, and, where appropriate, choose British culture essays within that discipline.

Personalized Learning

Students put together a combination of courses to meet particular needs and interests. Selecting a primary and secondary tutorial from the disciplinary lists, students normally do a research project that corresponds to the primary tutorial, and choose any British culture essays. This can be useful for meeting graduation requirements. Many students, however, find the programme works best when the various elements build on each other to make a coherent whole.

The tutorial is at the heart of the SCIO Semester Programme. It is an hour long conversation between a tutor who is engaged in research and one student who has spent the week reading and writing an essay in answer to a question.

The tutorial gives students the chance to read in depth, to formulate their views on a subject, and to consider those views in the light of the detailed, analytical conversation in the tutorial. Our aim is that through the tutorial experience, you can develop your ability to find your own ‘voice’ as a writer within your discipline. This means not simply relating the views and findings of others, but using them to develop your own opinions and justify your thoughts and conclusions. The one-on-one arrangement of the tutorial is particularly well suited to this.

For the semester-long programme, you have literally hundreds of different tutorial topics to choose from. You enroll in one primary tutorial which meets eight times and is worth six credits, and one secondary tutorial in a different topic; which meets four times and is worth three credits. More information on specific tutorials can be found below.

Primary Tutorial

6 Credits

Your primary tutorial meets each week (during the last 8 weeks of the fall semester and the first 8 weeks of the spring semester) for a total of 8 meetings. You’ll do assigned readings, conduct research, and write essays each week in preparation for your tutorials.

Secondary Tutorial

3 Credits

Your secondary tutorial meets every other week (during the last 8 weeks of the fall semester and the first 8 weeks of the spring semester) for a total of 4 meetings. Aside from the subject, secondary tutorials have all the same characteristics as primary tutorials.

Study

A semester at SCIO is an intensive study experience. While all majors may apply, you should look through our course offerings to see what the options are for each course.

A semester at SCIO is an intensive study experience. While all majors may apply, you should look through our course offerings to see what the options are for each course.

The main difference between U.S. and Oxford academics is Oxford’s acclaimed tutorial system: a series of hour-long sessions in which you and your tutor, one-on-one, will focus with undivided attention on your response to a single, daunting prompt. This is the system students often describe as the most intimidating and satisfying academic experience of their lives. It will change the way you read books, write sentences, and think—and students will often return home feeling like athletes who have trained at high altitude.

In addition to tutorials, all students will work on a semester-long research project on a topic of their choosing. Guided by an assigned research superviser, you will formulate a research question, plan your research paying particular attention to questions of sources, method, and approach, and write a paper in an appropriate academic voice. The process offers training in preparation for the rigorous research and writing required of a graduate student.

You will also have the opportunity to learn more about a particular area of British culture, through our Selected Topics in British Culture course. You will examine aspects of past and present-day Britain, either with direct studies of its society and culture or through its novelists and philosophers, artists, poets, mystics, and myth makers. You will have a chance to approach your chosen topic both in and outside the classroom – through discussion in small groups, analysis of texts, and field trips to iconic places outside Oxford, such as Stonehenge, Portsmouth, or Hampton Court.

Housing

SCIO’s student residence is The Vines, a late-Victorian mansion on Headington Hill overlooking Oxford’s “dreaming spires.” All SCIO students will be housed in The Vines. In addition to student rooms, the house also has large common spaces where students can work, study, and live. It also has a substantial garden where, when the weather is accommodating, students can relax and read, and, play sports.

SCIO places great significance on nurturing the student community that develops over the course of the semester. The program is academically demanding, and the support network that develops between all the students is essential in helping everyone feel that they are staying on top of things! Every semester many students have shared that over their time in Oxford they have formed some of their strongest ever friendships. The opportunity to live with like-minded people in one of the most beautiful cities in the world is exciting, profound, and fun.

Students accepted into the programme will complete a rooming preference questionnaire that helps SCIO place students in the most suitable room available. Most rooms are shared with 1-3 other students, but a small number single rooms are also available.

SCIO is a member of ANUK/National Code. More inforamtion about the National Code can be found in the below section on further information for the Vines.

THE VINES

The Vines, a modest mansion on the crest of Headington Hill, is situated on 1.5 acres of garden with stunning views of Oxford’s spires. Running parallel to the path of C.S. Lewis’s former commute, The Vines is a 35-minute walk into Oxford city centre, a 10-minute cycle ride, or a 5-minute walk to the nearest bus stop (with buses passing by every 6–7 minutes). The Vines will be your home away from home during the programme.

The Vines is equipped with the following ammenities:

- Free laundry facilities

- Library with work stations and free printing facilities

- Large common room

- Dining room

- Large kitchen

- Wheelchair access and disability accommodation

- Prayer room

- Free WiFi throughout the property

Further information and pictures of The Vines

SCIO is a member of ANUK/National Code which promotes high standards in private rented residential accommodation. In student housing matters, SCIO abides by the Code’s guidelines on equality, and works to ensure that no person will be treated less favourably than any other person or group of persons on grounds of race, colour, ethnic or national origin, gender, disability, appearance, age, marital status, sexual status, or social status. In addition, at The Vines and its Lodge, SCIO abides by the National Code’s standards for larger residential developments which governs practical matters. Its performance, with respect to equality in housing matters and to practical matters at The Vines and its Lodge, is regularly reviewed by an independent assessor approved by ANUK/National Code.

The Vines has been adapted to accommodate students with physical disabilities. This includes the following ground floor facilities: accessible single and double occupancy rooms, an accessible bathroom, all common rooms, kitchen, and both main entrances are equipped with ramps for wheelchair access. SCIO is committed to making reasonable arrangements to enable students to participate as fully as possible in all areas of the programme. Further information about accessibility accommodations are available upon request. Please send any queries to globaled@cccu.org.

The Vines is mixed gender housing, with both single and shared rooms available. Students are only assigned roommates of the same gender and, likewise, bathrooms facilities are only shared with students of the same gender.

Bedrooms

Students are placed in rooms based on their answers to a housing questionnaire that is part of the application process. Rooms range in capacity from singles to quadruples. Below are some examples of typical rooms in the Vines:

|

|

Common rooms

In addition to students bedrooms, there are many common rooms that are shared with everyone living at the Vines. At the Vines offers areas for students cook, study, and relax together in a tight knit community.

|

Lounge room |

Library and study room |

Kitchen |

Dining room |

The grounds

Students have full access to the grounds at The Vines. This includes a large back garden with tables and chairs for studying and eating and plenty of space for sporting activities and relaxing.

|

|

Internet Access

Free high speed broadband internet is available throughout the Vines. Login information for the Vines will be provided to you when you move in and is posted throughout the property. The wireless network is checked at regular intervals to ensure there is proper coverage throughout the property.

Environmental Sustainability at the Vines

SCIO is committed to reducing our environmental impact and we encourage our students to follow sustainable practices. We do this through:

- Providing recycling and composting bins and guidance on how to properly recycle at our student housing. Instructions for what can be recycled and composted is posted on the notice board by the main kitchen. An orientation about recycling and composting will be provided by the Junior Dean during the start of the programme.

- Encouraging students to walk and cycle while travelling around Oxford and to take mass public transit while traveling greater distances. The Vines provides ample secure bicycle parking for students that choose to get a bicycle while on the programme.

Libraries and Special Collections

Students on the Oxford Semester Programme have access to one of the greatest libraries in the world. Make use of Bodleian libraries and its large and rapidly growing physical and digital resources.

Additionally, Oxford’s museums and collections are world renowned and provide an important resource for scholars around the world.

Museums and Special Collections

- The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology houses the University’s extensive collections of art and antiquities. Established in 1683, it is the oldest museum in the U.K. and one of the oldest in the world. It also houses an exceptional collection of prints which can be viewed by any member of the public upon special arrangement. Free admission.

- The University Museum of Natural History houses the University’s scientific collections. With 4.5 million specimens it is the largest collection of its type outside the national collections. Free admission.

- The Pitt Rivers Museum holds one of the finest collections of anthropology and archaeology. Free admission.

- The Museum of the History of Science is housed in the world’s oldest surviving purpose-built museum building. It contains an excellent collection of historic scientific instruments from around the world. Free admission.

- The Bate Collection of Musical Instruments celebrates the development of musical instruments in the western classical tradition from the medieval period to the present.

- The University of Oxford Botanic Garden is the oldest botanic garden in Britain. It contains the most compact yet diverse collection of plants in the world.

- The Harcourt Arboretum is an informal garden, where the public can enjoy walks and riding their bicycles. It is six miles south of Oxford and forms an integral part of the Botanic Garden’s plant collection.

- The Christ Church Picture Gallery houses an important collection of Old Master paintings and almost 2,000 drawings in a gallery of considerable architectural interest.

- Modern Art Oxford is the largest collection of modern and contemporary art in the Southeast region of Britain. Admission free.

Spiritual Life

SCIO’s spiritual mission is first to demonstrate that personal faith in Christ can flourish within an academically rigorous environment; can operate in a public university; and interacts with scholarship but not necessarily in ways that are obvious and easily labelled. Second, to help students acquire the maturity, vision, confidence, and skills to study in the public research university and to encourage scholarly reflection in religious contexts and in a public, non-religious environment.

SCIO’s spiritual mission is first to demonstrate that personal faith in Christ can flourish within an academically rigorous environment; can operate in a public university; and interacts with scholarship but not necessarily in ways that are obvious and easily labelled. Second, to help students acquire the maturity, vision, confidence, and skills to study in the public research university and to encourage scholarly reflection in religious contexts and in a public, non-religious environment.

Learning to study alongside and under those of different religious beliefs (or, in many cases, none) is challenging. We encourage this by offering ourselves as mentors/examples, creating an atmosphere of independence in which students can develop such a vision and ability, and offering nurture by staff who are engaged and committed.

All students are encouraged to find a church home in Oxford. Apart from the spiritual nourishment that comes from remaining involved in regular worship, church is a great place to meet other students and residents of the town, and creates opportunities for you to get to know the people in your community. Many students on the programme make a point of attending a church whose style is markedly different from that which they usually attend at home, while other students find it a great comfort to attend a service whose style is more familiar, and all students should think about what might best suit them while they are here.

Exploring

Exploring

Alongside the field trips organized as part of the programme, there are opportunities for students to explore other parts of the UK. The costs associated with non-academic trips are the responsibility of each student. In the past, these outings have proven to be a great break from studying and a chance to explore more of the British landscape. You may also wish to follow an itinerary below on your own or with a friend!

Exploring Oxford and Beyond

Oxford

Oxford is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. While in Oxford you will have access to libraries that have been established for over 800 years, as well as the city’s its museums, bookshops, and entertainment venues. Discover some of the amazing art available on view in Oxford with an art-walk: explore Christ Church Picture Gallery, see the Pre-Raphaelite murals in the Oxford Union, and visit the famous “Light of the World” by Edward Burne-Jones hidden away in the chapel at Keble College. Over your time at Oxford, various plays are put on in the evenings, which are fun to attend as a group.

Blenheim Palace

Spend the day wandering the grounds of Blenheim Palace: a world heritage site, home of the eleventh duke of Marlborough, and the birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill. The palace dates from 1705 and is set in a park designed by Capability Brown. Next to the grounds is the village of Bladon, where we visit Winston Churchill’s grave. Complete the afternoon with tea at the wonderful Bladon Tea Rooms in Woodstock.

Port Meadow

Enjoy a beautiful afternoon stroll (weather permitting) through Oxford’s Port Meadow—frequented by grazing horses—and end at the famous Trout Inn for a meal of fish and chips.

Bath

Stroll through the Roman streets of Bath, taking in all of its architectural beauty. Visit the Roman Baths and the great Abbey, and follow in the footsteps of one of Bath’s most famous inhabitants, Jane Austen. End the day with tea at Sally Lunn’s tea-room in the oldest house in Bath.

C.S. Lewis’s Home

Enjoy an afternoon visit to The Kilns, C.S. Lewis’s home in Headington. After touring the house and grounds, visit his parish church, Holy Trinity, where he is buried and commemorated with beautifully etched Narnia windows.

Burford

Burford is a small historic village with one of the most prized parish churches in the country, dating from the 1100s (although the site has been a place of Christian worship since the 600s). Walk through the countryside to visit the deserted medieval village of Widford, a once-thriving community that was wiped out by the plague during the 14th century and never recovered. The 12th-century church is all that remains, and is situated in the middle of a field without any access except by foot.

Dorchester

Once a major political and ecclesiastical centre, Dorchester is now a sleepy town with one of the most fascinating churches (once an abbey) in the country. Walk through the woods and up an Iron Age hill fort (dating from the 4th century BC) with some of the most spectacular views in Oxfordshire. Plus another 14th-century church to explore along the way! Cross the Little Wittenham Bridge, used for the official World Poohsticks Championships.

London

Over the semester many students find themselves drawn to sites and attractions in London, which is less than an hour by train, or 90 minutes by bus. In one day, students often manage to explore aristocratic London and the royal parks, and go past Buckingham Palace, Big Ben, Westminster, and Downing Street before stopping to spend some time in the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery at Trafalger Square. After lunch, you can walk around some of the older part of the City of London, including an optional climb up the Monument (a large Corinthian column with panoramic views over London from its top) and a walk past the Tower of London and Tower Bridge. Then go to St Paul’s Cathedral for evensong, where you can hear one of the finest all-boys choirs in the world. Don’t forget to have dinner before heading back home. Phew! And that is only a minute selection of the many opportunities there are to explore whatever might be your heart’s desire in this remarkable city. Some students have chosen to supplement their research by taking advantage of their free access to the holdings of the British Library in London and the National Archives at Kew, near London.

JCR Committee

The JCR committee is a distinctly Oxford institution and stands for the Junior Common Room. The JCR committee for the Semester Programme is a group of five to seven students from the programme — voted onto the committee by you once you have arrived — who help run fun events for all the Semester Programme students. It is always great fun to be part of the JCR committee, as you get a chance to make things happen the way you would like! The JCR committee has a sizable budget to help fund its various activities. Every JCR committee has its own way of running things, but usually every semester we have a variety / open mic night which showcases your talent. The JCR committee can also help organize activities that give you a chance to give something back to the community by helping in various charitable ways.

Sports

Every semester students enjoy competing alongside other students in Oxford in the various sports that take place while they are here. Sports that you can play include basketball, volleyball, football (soccer), archery, fencing, rowing, and table tennis. Nearly any sport that you enjoy is represented in Oxford.

Clubs and Societies

Clubs and Societies

Oxford has hundreds of clubs and societies that cover almost any activity you can think of. There are several orchestras of varying standards and many choirs (some you have to audition for and some you do not). If you enjoy acting, why not audition for a role in a play? Juggling, dancing, hiking, caving, movies, politics, debating…you name it, there is a club somewhere in Oxford where you can meet other students with similar interests. There are also numerous Christian societies and activities going on throughout the city, and you will find that you are always welcome to participate while you are here.

Weather

Be prepared for all types of weather over your semester in Oxford. There will be sunny stretches when you can read and study outside in the sleepy warm sunshine, and other times when you can have a snow fight in the University parks! Whatever happens, you can guarantee that it will rain, so pack waterproof clothing.

Tea (and Food)

Drinking tea is a vital element in the rhythm of the English person’s day, and all students are encouraged to discover this for themselves. Its popularity is perhaps explained in part by the cakes and biscuits that traditionally accompany this drink. Students will be invited to tea at regular times during the week, and it is an important time to relax, catch up with each other, and recharge for the rest of the day!

Drinking tea is a vital element in the rhythm of the English person’s day, and all students are encouraged to discover this for themselves. Its popularity is perhaps explained in part by the cakes and biscuits that traditionally accompany this drink. Students will be invited to tea at regular times during the week, and it is an important time to relax, catch up with each other, and recharge for the rest of the day!

Apart from some lunches organized as part of the program, all students will need to prepare their own meals while in Oxford. This means shopping at one of the main supermarkets, going to the weekly fresh farmer’s market, or visiting the Covered Market, established in 1774. Many students form food groups that take turns to cook for each other and eat together at the end of each day. It is a great way to share with others what they have discovered that day, and also to hear what everyone else has been doing!

There are plenty of places to eat out in Oxford, ranging from the affordable to the expensive. The café in St Mary’s Church is a fun place to visit, as the café itself is in the Old Congregation House, and was the University’s first “official” building. It dates from the 14th century and was built a couple of hundred years after the colleges first started taking in students.

Alumni

When the semester is all said, done, debated, and graded, you’ll return home with a community of alumni that continually reconnect over the bond that Scholarship and Christianity in Oxford so passionately unites. Learn more about what alumni are up to on the SCIO website.

The SCIO Semester Programme is an interdisciplinary program that gives no preference to students in any particular field of study. However, a good academic record is necessary.

Students must have a GPA of 3.7 or higher or an overall minimum 3.5 GPA with a minimum GPA of 3.7 in their major.

The tutorial style of teaching is very different from the North American system of education; many students find this a stimulating and challenging transition, requiring experience and maturity. The tutorials, lectures, and seminars are equivalent to upper-division courses. Students are expected to do advanced-level work, and therefore need to have sufficient preparation for the concentration chosen.

It is advised that students participate in their junior or senior year; however, if your academic (curricular or extracurricular) schedule won’t allow you to come to SCIO in your junior or senior year, you can apply for admission as a sophomore (second-semester encouraged). The programme coursework will be no less demanding, but, in a tutorial (just one student and a tutor), it is always possible to tailor the teaching to the student.

SCIO aims to provide an inclusive environment which promotes equality, values diversity, and maintains a working, learning and social environment in which the rights and dignity of all its staff and students are respected to assist them in reaching their full potential.

For more information on the the SCIO Semester Programme, contact admissions@cccu.org, or phone 202-552-3974.

How Do I Apply?

Simply complete an online application for the semester during which you plan to participate. Each campus makes its own policies regarding off-campus study, so you should consult your academic dean, off-campus study coordinator, and/or advising faculty member at your school to ensure completion of all campus requirements.

Before your application can be reviewed for admission, you must submit all of the following materials:

- Completed online application form

- $50 application fee (payable by check or credit card)

- 1 faculty reference

- 1 character reference

- 1 honors director or department chair approval

- Official transcript(s) of all college course work

After Acceptance:

Once admitted into the program, you will be required to confirm your intent to participate by submitting a non-refundable $500 confirmation fee, which will be applied toward your program tuition.

You will also be required to complete additional confirmation and pre-departure materials, including but not limited to: waiver and liability forms, a medical information form, a housing form, and proof of international medical insurance. But don’t worry! We will send you all the details and instructions on your acceptance.

SEMESTER PROGRAMME DATES

Fall 2026

Rolling Admissions

| Application available until (or spots are filled) | May 1 |

| SCIO begins on arrival | Sep 4 |

| SCIO concludes | Dec 14 |

Spring 2027

Rolling Admissions

| Application available until (or spots are filled) | Nov 1 |

| SCIO begins on arrival | Jan 8 |

| SCIO concludes | Apr 19 |

HOW MUCH DO I PAY & WHAT’S INCLUDED?

Deposits:

Typically, the only expenses SCIO Semester Programme participants pay directly to the CCCU are the application fee ($50) and the non-refundable confirmation fee ($500, deducted from the total housing fee at invoicing).

Program Fees:

About six weeks before each semester begins, the CCCU sends participation invoices to each home campus. For the 2025-26 school year, that bill will feature the below SCIO Semester Programme costs.

| SCIO SEMESTER PROGRAMME FEES | |

|---|---|

| Instructional Fees | $16,000 |

| Room | $3,950 |

| TOTAL SEMESTER FEES | $19,950 |

| Confirmation Deposit | ($500) |

| BALANCE OF SEMESTER FEES | $19,450 |

Keep in mind the total program costs billed to you through your school may differ, depending on your campus’s policies.

Note: Schools or individuals who pay with a credit card will also be charged a credit card service fee.

Expenses Covered by the SCIO Semester Programme Fees:

- 17 hours of academic credit

- Accommodation in SCIO’s student housing

- Grade report from SCIO

- International medical coverage for the duration of the semester

- Field trips to historical destinations of academic interest

- Access to the Bodleian libraries

- Use of programme computers, unlimited wireless internet access, and printing facilities

- Free on-site laundry facilities at the Vines (must provide own detergent, etc.)

- Social events including weekly afternoon teas with staff and other funded student events

Additional Anticipated Expenses:

- Travel to and from and Oxford

- Meals

- Books

- Personal medical expenses, if incurred, including preparatory vaccinations

- Personal discretionary expenditures

- Local transportation

International Travel

Participants are responsible for arranging travel to and from Oxford. Student housing check-in time is between 9am and 5pm on arrival day; departure is before 11am on checkout day. Student accommodations are closed outside of official program dates/times. Travel information from London’s major airports to SCIO’s student housing is provided in a pre-departure packet.

HOW DOES BILLING WORK FOR SCIO SEMESTER PROGRAMME PARTICIPATION?

The SCIO Semester Programme is an extension campus of each member institution of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities (CCCU); each school grants the academic credit for program participation.

The CCCU invoices campuses for the cost of participation in the SCIO Semester Programme and in turn campuses bill their students following the campus’s established policies and procedures. (For example, some schools charge the exact fees of the off-campus program, other schools charge the campus tuition price, while others charge full on-campus fees plus an additional off-campus study fee. And there’s every variation in between!)

Since each school determines their own policies regarding off-campus study costs and the applicability of institutional scholarships and other aid, you should confirm your school’s policies with the Off-Campus Study Coordinator on your campus.

Learn More

SCIO Staff Support

Staff at SCIO are available and equipped to provide support for students. Our staff have decades of experience working with study abroad students in Oxford as well as other locations around the world. SCIO has staff members that are trained in mental health first aid and medical first aid. Where needed, SCIO has relationships with local counselling services to refer students that need to meet with a counsellor while in Oxford.

Nightline Oxford

Nightline is a listening, support, and information service run for and by students, and it aims to provide every student in Oxford with the opportunity to talk to someone in confidence. They are available to everyone from 8:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m., but only during Oxford term time. Nightline does not provide advice or tell callers what to do; it is a service that listens and talks about whatever the caller wants, big or small, in complete confidence. Nightline also offers a wide range of information related to mental health and general health issues. Students can contact Nightline from 8:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m. by phone (01865 270270) or in person.

Health Services

There are a number of world-class professional medical, surgical, and psychiatric facilities located in Oxford. International emergency medical insurance is provided for all students on the programme, but this may not cover all costs of medical care. Students will be responsible for covering the costs of any medical costs that are not covered by insurance. Some universities provide assitional medical insurance for their students. Students should enquire about this with the off-campus study office at their home university. General pastoral care and support is provided by SCIO staff, who can also assist in helping students get connected to needed medical care.

Know Before You Go

Studying off campus can be an exciting time filled with adventure and personal growth. Prepare yourself in advance for challenges you might face on the programme. Students at SCIO should anticipate:

- Walking in and around the city may include uneven terrain, such as cobblestone walkways, in unpredictable weather and frequent rain.

- Living in a residence of multiple occupancy with shared bathrooms, kitchens, and communal spaces. Living (and other) spaces are not air-conditioned, though this is very rarely problematic in the cool British summers. Living and other spaces are heated in winter.

- The Vines is located on a hill from which Oxford city centre is accessible via a 35-minute walk, a 10-minute cycle ride, or a 20-minute bus ride accessed via a 5-minute walk to the nearest bus stop (with buses passing by every 6–7 minutes). The Vines has a bathroom for use by students in wheelchairs and generally with limited mobility and can offer ground floor accommodation.

- Students are responsible for purchase and preparation of their own food and transportation.

- Traffic drives on the left side of the road.

- Students may be unused to cycling or to cycling in traffic and this should be considered before cycling in Oxford.

- Historic buildings can present difficulties to students with mobility challenges but professional staff help with such challenges.

- Living away from family, friends, and other support networks.

- Managing and following a demanding study schedule with substantial independence, and attending lectures, one-on-one tutorials, and day-long field trips.

- Experiencing potentially challenging personal, religious, and cultural learning, lectures, field trips, and assignments.

Safety

Oxford is generally a safe place in which to study and explore; nevertheless, you should minimize any risks by remaining alert and taking precautions. Students will be briefed about safety protocols during programme orientation. You can also familiarize yourself with any current travel or health advisories for the United Kingdom by visiting the U.S. State Department and Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) websites.

Many of the faculty and staff have lived in Oxfordshire for years. During orientation, we will discuss basic guidelines to follow to help you feel confident and safe during your time here. If you have any questions prior to departure, please contact your admissions advisor.

PROGRAMME LOCATION

You’ve probably heard a great deal about the UK, but what makes Oxford stand out? Read the FAQ below to find out.

Where does the programme take place?

The programme is located in Oxford, one of the oldest and most prestigious university cities in the world. You will study in and enjoy all the benefits of the great city of Oxford. The SCIO offices are in North Oxford, a 15 min walk to the city centre. The Vines is located in the Headington neighborhood, a 30 min walk to the city centre.

Oxford is located 60 to 90 minutes from the centre of London by train or bus.

Will I get to travel throughout the semester?

What is the climate like?

What is the geography like?

ACADEMICS

SCIO revolutionizes the way students learn — the way they read books, write essays, make arguments, and think. Are you ready to enter this gauntlet and emerge as a newly minted scholar? Read the FAQ below to find out more.

How many credits will I receive?

How will my courses be transferred back to my home university?

Where will I be taking classes?

For tutorials, students may meet with their tutors at their college or department, while others meet at SCIO’s offices, museums, coffee shops, and other places in Oxford.

For the British Culture courses and Research Prohect meetings, most of these will take place at SCIO’s offices, which has teaching room space.

What will I be studying?

You will be in four courses throughout the semester. The heart of the Oxford Semester Programme is the tutorial. During the full eight-week Oxford term, you will be enrolled in a primary (6 credits) and a secondary (3 credits) tutorial, which meet every week and every other week, respectively.

The British Culture course (4 credits) examines aspects of past and present day Britain. Students attend discussion and gobbets (gobbet is Oxford’s word for a small mouthful of text for close reading or translation and then discussion) classes in the tutorial seminar of their choice and participate in field trips, but spend most of their time doing independent study to produce detailed, scholarly essays. The Research Project (4 credits) allows for independent research on a topic of students’ choosing. Most of the work for the Research Project is independent research, but each student is assigned an advisor to guide them in their research.

Who will be teaching my classes?

Who will be in my classes: local or CCCU GlobalEd students?

TRAVEL

What do you need to know before you step on that plane? Read the FAQ below to find out!

How will I get to and from the programme?

Will I need a passport?

Will I need a visa?

Will my family and friends be able to visit me during the semester?

DAILY LIFE

Students are sometimes surprised by how different day-to-day life in Oxford can look. In this FAQ series, we’ll answer some common questions about living in Oxford.

Where does a typical week look like?

Throughout the semester we have weekly tea on Tuesdays in the SCIO offices. This is a time for students and staff to come together, take a break from study, and get to know each other better. These teas are often a highlight of the semester for both students and staff. During the tutorial period we also have weekly gatherings as part of our Vocation and Scholarship series. The aim of this series is to provide a platform for exploring the idea of vocation within a culture of research and scholarship. These meetings take the form of either an academic lecture or chapel service.

During the tutorial period, you will only meet once or twice with your tutor each week and the rest of your week is spent preparing for your upcoming tutorials. Some students prefer to study at the Vines, either in their room or the common areas, some prefer to study in one of the Bodleian libraries, and others enjoy studying in the student lounge of the SCIO offices. Regardless of your preferred place of study, the tutorial sytyle of learning is very self-directed and emphasizes individual study over classroom time.

During the Selected Topics in British Culture period, you will have more frequent small group, discussion based classes. We will also have weekly filed trips to various sites around England.

You will also be working on your research project throughout the term, so will need to make sure you allocate time to work on that alongside your other coursework.

In addition to your academics, you may choose to get involved in the numerious clubs and societies on offer in Oxford. Theses are a great way to get to know other students in the city and engage with those in the local community.

Where will I live?

The Vines, a modest mansion with a beautiful view, is a 35-minute walk to the city centre of Oxford. It also has a common room, dining room, large kitchen, and laundry facilities.

If you are accepted to the programme, you will be asked to fill out a housing form in which you may indicate any rooming preferences you have. However, please bear in mind that SCIO will not always be able to accommodate housing preferences.

What will I eat?

You will get plenty of invites to tea times throughout the week. Many students acquire such a taste for tea, and for the social rejuvenation of these respites, that they bring the custom back home at the programme’s end.

How will I get around?

For travel outside of Oxford, the UK has an extensive network of trains and buses that can get you to most anyplace you will want to visit.

Will I be interacting with local people?

Will my cell phone work in England?

If your phone is unlocked and compatible with overseas SIM cards, you can purchase this card upon arrival. Many students choose this option as it is often much more cost effective than paying to use your US provider’s service in the UK.

COMMUNITY AND SPIRITUAL LIFE

As you prepare for this uniquely challenging opportunity, know that you are not alone. Oxford and its faculty, staff, and fellow scholars will join you and equip you as you face the challenges—and celebrate the gifts—of life as a student in Oxford. Read these FAQs to find out more about the community and spiritual life of the SCIO Semester Programme.